The nice folks at Industry Week have posted “Turning Yourself In: Export Enforcement Trends,” an article by me on the EP MedSystems case and the benefits (or not) of voluntary self-disclosures.

The nice folks at Industry Week have posted “Turning Yourself In: Export Enforcement Trends,” an article by me on the EP MedSystems case and the benefits (or not) of voluntary self-disclosures.

Archive for March, 2007

7

“Turning Yourself In”

Posted by Clif Burns at 9:07 am on March 7, 2007

Posted by Clif Burns at 9:07 am on March 7, 2007 Category: General

Category: General

Permalink

Permalink  Comments Off on “Turning Yourself In”

Comments Off on “Turning Yourself In” Copyright © 2007 Clif Burns. All Rights Reserved.

(No republication, syndication or use permitted without my consent.)

6

“Whatever It Takes”

Posted by Clif Burns at 3:40 pm on March 6, 2007

Posted by Clif Burns at 3:40 pm on March 6, 2007 Category: BIS

Category: BIS

The Bureau of Industry and Security (“BIS”) released today a notice of a final rule amending certain of the rules relating to crime control commodities. Items covered by BIS’s crime controls are controlled because of the fear that these items will be used for torture and other human rights violations. Three parts of the new rule seem worthy of comment.

The Bureau of Industry and Security (“BIS”) released today a notice of a final rule amending certain of the rules relating to crime control commodities. Items covered by BIS’s crime controls are controlled because of the fear that these items will be used for torture and other human rights violations. Three parts of the new rule seem worthy of comment.

First, the new rule amends the classification for thumbcuffs. Thumbcuffs have been moved from ECCN 0A982 to ECCN 0A983. the reason for the change is the stricter licensing policy applicable to items in ECCN 0A983. Items in ECCN 0A983 are subject to a general policy of denial whereas items in ECCN 0A982 are subject to favorable case-by-case consideration unless there is civil disorder or a history of human rights violations in the country to which the cuffs are being exported. (Newlyweds with adventurous tastes might keep this in mind when packing for their honeymoon, since the License Exception BAG, which covers personal effects carried in baggage, doesn’t apply to ECCNs 0A983 or 0A982.)

Second, the new rule amends section 740.2(a)(4) of the EAR — which eliminates the use of license exceptions in most instances for exported goods subject to crime controls. The new rule replaces the word “commodities” in the prior version of the rule with the word “items.” The purpose of this change was to make clear that the restrictions of section 740.2(a)(4) apply to software and technology and not just to physical commodities.

Finally, the new rule amends section 740.2(a)(4) to allow license License Exception GOV to be used for exports of crime control items to U.S. government personnel and agencies. BIS’s notice of the Final Rule explained this change as follows:

Although this change applies to any U.S. Government agency, BIS is making it at this time because of the need to supply U.S. armed forces in locations that, prior to publication of this rule, would be subject to the geographic restriction on use of License Exceptions for crime control items.

Okay, now everyone who believes that, raise your hands. Hmm. I only see a couple of hands. Now, everyone who believes that the purpose of the change is to permit exports of crime control items to U.S. government employees using “enhanced interrogation techniques” on suspected terrorists, raise your hands. Just what I suspected. A lot more of you have raised your hands. Of course, we can’t be sure that this was BIS’s motivation but we can be sure that if it was, BIS wouldn’t say so.

Permalink

Permalink  Comments (2)

Comments (2) Copyright © 2007 Clif Burns. All Rights Reserved.

(No republication, syndication or use permitted without my consent.)

5

A Penalty Is Only a Penalty, But a Good Cigar Is a Smoke

Posted by Clif Burns at 4:36 pm on March 5, 2007

Posted by Clif Burns at 4:36 pm on March 5, 2007 Category: Cuba Sanctions

Category: Cuba Sanctions

The ninth annual Habanos Festival just wound up in Havana. The festival, a five day celebration of Cuban cigars, attracts cigar enthusiasts from all over the world — including the United States.

The ninth annual Habanos Festival just wound up in Havana. The festival, a five day celebration of Cuban cigars, attracts cigar enthusiasts from all over the world — including the United States.

You really have to like Cuban cigars to risk receiving a nastygram from OFAC demanding hefty fines for violations of the U.S. embargo on Cuba. And most Americans who sneak into Havana through Canada or Mexico are smart enough to pretend to be Canadian when approached by reporters. Most, but not all. This year a heart surgeon and professor at Stanford volunteered his name to reporter from the South Florida Sun-Sentinel and said this:

“We don’t do anything illegal against the government policies,” said [name redacted by ExportLawBlog], 45, a heart surgeon and Stanford University professor from San Jose. “But I think to visit any country is the basic right of a human being. We are not taking in any contraband. We just enjoy and finish the cigars here and we go back.”

“I don’t see it as a violation,” he said, echoing other Americans at the festival. “It’s a personal right.”

I’ll make a deal with the good doctor. I’ll agree to not perform heart surgery if he’ll agree not to practice law.

(With apologies to Rudyard Kipling for the title.)

Permalink

Permalink  Comments Off on A Penalty Is Only a Penalty, But a Good Cigar Is a Smoke

Comments Off on A Penalty Is Only a Penalty, But a Good Cigar Is a Smoke Copyright © 2007 Clif Burns. All Rights Reserved.

(No republication, syndication or use permitted without my consent.)

2

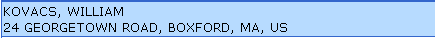

Where in the World Is William Kovacs?

Posted by Clif Burns at 12:32 pm on March 2, 2007

Posted by Clif Burns at 12:32 pm on March 2, 2007 Category: BIS

Category: BIS

In an earlier post, we took the Bureau of Industry and Security (“BIS”) to task for filing a default motion against William Kovacs to deny his export privileges even though he was in jail for his export violation and his ability to respond to BIS’s default motion would be, well, limited. We also felt pretty sure that BIS knew where he was, because BIS’s own reports on the case indicated that Kovacs had been incarcerated.

In an earlier post, we took the Bureau of Industry and Security (“BIS”) to task for filing a default motion against William Kovacs to deny his export privileges even though he was in jail for his export violation and his ability to respond to BIS’s default motion would be, well, limited. We also felt pretty sure that BIS knew where he was, because BIS’s own reports on the case indicated that Kovacs had been incarcerated.

Well, maybe BIS doesn’t really know where Kovacs is. Today BIS updated the Denied Party List (the “DPL”) and here is the entry for Kovacs:

That’s his old home address.

We might give BIS for some slack over its confusion about the real location of William Kovacs were it not for the Bureau of Prisons Inmate Locator which you can find here. Enter Mr. Kovacs’s name and the Inmate Locator will serve up a result page showing that he is currently inmate 24999-038 at the Fort Dix Federal Correctional Institute in New Jersey.

So, here’s my question. William Kovacs is a fairly common name. Suppose that an international courier service got a package from Mr. Kovacs with a gift for his favorite aunt in London. The courier checks the DPL and finds only a William Kovacs at a street address in Boxford, Massachusetts, so the courier goes ahead and ships the package. Has the courier violated BIS rules?

Now, I have suggested before that a prison address might be a red flag. But in other instances, BIS has gone out of its way to list, even to correct, prison addresses and inmate numbers on the DPL. There certainly seems no reason that they haven’t done that here.

Permalink

Permalink  Comments Off on Where in the World Is William Kovacs?

Comments Off on Where in the World Is William Kovacs? Copyright © 2007 Clif Burns. All Rights Reserved.

(No republication, syndication or use permitted without my consent.)

Search Site

Links

DDTCBIS

OFAC

Foreign Trade Division

SIA

Export Practitioner

ABA Export Controls & Economic Sanctions Committee

Resources

Get Global PresentationITAR

EAR

SDN List

Entity List

Debarred List

Categories

Agricultural ExportsAnti-Boycott

Armenia

Arms Export

BIS

Burma Sanctions

CCL

CFIUS

China

Criminal Penalties

Cuba Sanctions

Customs

DDTC

Deemed Exports

DoJ

Economic Sanctions

Encryption

Entity List

EPA

Eritrea Sanctions

EU

Export Control Proposals

Export Reform

FCPA

FDA

Foreign Countermeasures

Foreign Export Controls

General

ICE

INCOTERMS

India

Iran Sanctions

ITAR

ITAR Creep

Libya Sanctions

MTCR

NASA

Niger

Night Vision

Nonproliferation

North Korea Sanctions

NRC

OECD

OFAC

Part 122

Part 129

Piracy on the High Seas

Russia Designations

Sanctions

SDN List

SEC

SEDs

Somalia Sanctions

Sudan

Syria

Technical Data Export

Technology Exports

TSRA

U.N. Sanctions

USMIL

USML

Venezuela

Wassenaar

Zimbabwe Sanctions

Blogroll

Customs & Int'l Trade LawExport Control Blog

Int'l Trade Law News

Census Blog: Global Reach

Subscribe

To subscribe to email notices

of new posts, click the

following link:

Subscribe to ExportLawBlog » Russia Designations

If you subscribed prior to January 4, 2011, unsubscribe

to email notices of new posts

by clicking the following link:

All other subscribers can unsubscribe by clicking the unsubscribe link in notification emails.