![By U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Jesse B. Awalt/Released (DefenseImagery.mil, VIRIN 090202-N-0506A-724) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AOmar_al-Bashir%2C_12th_AU_Summit%2C_090202-N-0506A-724.jpg By U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Jesse B. Awalt/Released (DefenseImagery.mil, VIRIN 090202-N-0506A-724) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AOmar_al-Bashir%2C_12th_AU_Summit%2C_090202-N-0506A-724.jpg](https://www.exportlawblog.com/images/al-bashir.jpg)

ABOVE: Omar Al-Bashir

From news that appeared to break recently in the Sudanese press, Sudanese President Omar Hassan al-Bashir submitted a visa application to the U.S. State Department in order for him to attend UN General Assembly meetings that begin next week. When asked about the application at Monday’s State Department press briefing, Deputy Spokesperson Marie Harf said, “We condemn any potential effort by President Bashir to travel to New York, given that he stands accused of genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Court. We would say that before presenting himself to UN headquarters, President Bashir should present himself to the ICC in The Hague to answer for the crimes of which he’s been accused.” Harf continued, “Clearly, we have a visa application right now and would condemn any potential travel by him, but I just don’t have anything further than that.” While it can be expected the State Department will have a concrete position by next week, this situation, and the U.S. response, could serve as an important juncture in U.S. sanctions against Sudan.

Although Syria, Iran and North Korea have attracted most of U.S. foreign policy’s attention in the past year, Sudan remains among the few countries under a comprehensive U.S. trade embargo. Sanctions against Sudan, however, continue to allow foreign subsidiaries of U.S. companies to do business there, and the sanctions themselves do not even apply in general to what the Sudanese Sanctions Regulations refer to as “Specified Areas of Sudan.” The Areas, most of which are along the Sudan-South Sudan border, are among the richest in oil and other natural resources in the entire country.

From a U.S. sanctions perspective, Sudan is more open for U.S. business than Iran. Yet since Bashir’s last trip to the United States in 2006, former Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad has attended UN meetings in New York on several occasions and even spoke at Columbia University. Although his trips were not without controversy, Ahmadinejad was still permitted to enter (and leave) the United States. Reactions from the State Department and Ambassador Samantha Power about Bashir’s visa request point out a difference that Bashir has a warrant issued for his arrest by the ICC, an organization incidentally to which neither Sudan nor the United States are parties. In short, Bashir is one of the most condemned sitting foreign leaders by the United States and most of the world. His visa request, therefore, invites comparison to those prior ones of Ahmadinejad and other leaders of sanctioned countries.

Whether Bashir, his regime and, by extension, Sudan should be subject to stronger sanctions like those against Iran is a debate for U.S. foreign policymakers that is not treated as a political priority at the moment. What is significant about Bashir’s visa request is that Bashir himself may be forcing the issue on the United States, notwithstanding the widespread violence that has continued in Sudan to the present. Issuing or denying a visa both carry significant foreign policy consequences and may lead to a closer examination as to what current U.S. sanctions and export control objectives are with respect to Sudan.

Clif adds: It should also be noted that a denial of the visa for Al-Bashir would be a violation of Article IV of the UN Headquarters Agreement, pursuant to which the United States committed not to impose any “impediments to travel” by “representatives of Members” to UN Headquarters “irrespective of the relations existing between” the United States and the country involved.

Posted by

Posted by  Category:

Category:

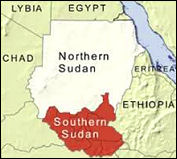

Even though the U.S. has lifted its Sudan sanctions with respect to the newly-minted state of South Sudan, that has not resolved the conundrum of U.S. oil investment and activity in South Sudan. South Sudan is land-locked, and all oil from South Sudan can be commercialized only by using a pipeline that runs through Sudan on its way to Port Sudan on the Red Sea.

Even though the U.S. has lifted its Sudan sanctions with respect to the newly-minted state of South Sudan, that has not resolved the conundrum of U.S. oil investment and activity in South Sudan. South Sudan is land-locked, and all oil from South Sudan can be commercialized only by using a pipeline that runs through Sudan on its way to Port Sudan on the Red Sea.  Today the Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”) released

Today the Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”) released  Yesterday provisional results were

Yesterday provisional results were  In the latest

In the latest