Last Friday the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit released its opinion in a case brought by the Al Haramain Islamic Foundation (“AHIF”) in which AHIF challenged its designation as a terrorist-supporting organization by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”). Although the court found that there was sufficient evidence to support OFAC’s designation of AHIF and its blocking of AHIF’s assets, it found that OFAC’s procedures were deficient and it remanded part of the case to the district court for further proceedings.

Last Friday the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit released its opinion in a case brought by the Al Haramain Islamic Foundation (“AHIF”) in which AHIF challenged its designation as a terrorist-supporting organization by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”). Although the court found that there was sufficient evidence to support OFAC’s designation of AHIF and its blocking of AHIF’s assets, it found that OFAC’s procedures were deficient and it remanded part of the case to the district court for further proceedings.

The first area in which the Ninth Circuit chided OFAC was in relation to OFAC’s reliance on confidential information to designate AHIF as a specially designated global terrorist (“SDGT”) under Executive Order 13,224 without providing any information to AHIF concerning that confidential information. While the court held that the government’s interest in national security and the prevention of terrorism did not require it to disclose the confidential information to AHIF or to not rely on undisclosed confidential information in making its determination, the court held that there were procedures short of those options that were mandated by the Due Process clause. Specifically, the Ninth Circuit noted that OFAC should provide, subject to exceptions for special cases, either an unclassified summary of the evidence or access to the evidence by an attorney with an appropriate security clearance.

The second area of criticism of OFAC by the court also related to the requirement of the Due Process clause and specifically to its requirement to provide to AHIF adequate notice of the basis for AHIF’s designation as an SDGT. The court noted that OFAC never supplied a statement of reasons to AHIF but only provided it with several unclassified documents and a request the AHIF supply OFAC with a copy of the Koran. (I must admit that I am completely baffled by OFAC’s Koran request. If, for some reason, OFAC needed to research Islamic principles a free copy of the Koran can easily be found for download at the Gutenberg Project in both a translation by J.M Rodwell and a translation by George Sale.)

Even though the Ninth Circuit found that OFAC violated AHIF’s Due Process rights, it declined to take further action on these violations on the basis that AHIF was not harmed by these violations. Basically, the court relied on the legal doctrine known as “guilty as hell.” In effect, the court said that AHIF was so clearly a terrorist-supporting organization that it would have lost even if OFAC had supplied a statement of reasons for the designation as well as an unclassified summary of the confidential evidence or access to that evidence by an attorney with a security clearance.

The third area in which the court took OFAC to task, and which resulted in the remand to the district court, was OFAC’s violation of AHIF’s Fourth Amendment rights by seizing AHIF’s assets through the blocking process without a judicial warrant. The court did credit OFAC’s concern with “asset flight” and permitted OFAC to initially seize assets without a warrant pursuant to the emergency exception to the Fourth Amendment. But that exception would still require a judicial warrant before the assets were permanently blocked.

This decision accords with a prior district court decision in the KindHearts case. Other district court have ruled that blocking assets isn’t a seizure because the government doesn’t take possession of the blocked assets, a strained rationale at best. See Islamic Am. Relief Agency v. Unidentified FBI Agents, 394 F. Supp. 2d 34, 47-48 (D.D.C. 2005); Holy Land Foundation for Relief and Development v. Ashcroft, 219 F. Supp. 2d 57, 79 (D.D.C. 2002). Because the Ninth Circuit’s rationale only applies to assets held by U.S. citizens, and because most blocked assets belong to foreign citizens, it is unlikely that this warrant requirement, even if followed by OFAC, would have a significant impact on OFAC’s practices.

Posted by

Posted by  Category:

Category:

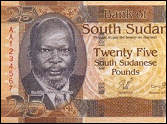

Even though the U.S. has lifted its Sudan sanctions with respect to the newly-minted state of South Sudan, that has not resolved the conundrum of U.S. oil investment and activity in South Sudan. South Sudan is land-locked, and all oil from South Sudan can be commercialized only by using a pipeline that runs through Sudan on its way to Port Sudan on the Red Sea.

Even though the U.S. has lifted its Sudan sanctions with respect to the newly-minted state of South Sudan, that has not resolved the conundrum of U.S. oil investment and activity in South Sudan. South Sudan is land-locked, and all oil from South Sudan can be commercialized only by using a pipeline that runs through Sudan on its way to Port Sudan on the Red Sea.  Only a few nanoseconds after JPMorgan Chase Bank

Only a few nanoseconds after JPMorgan Chase Bank  By now you’ve probably read the JPMorgan Chase Bank (“JPMC”)

By now you’ve probably read the JPMorgan Chase Bank (“JPMC”)