The Chi Mak case has engendered its fair share of confusion, and the latest victim is a trade law attorney who submitted a brief article to an export law newsletter that was published today. According to that article, the verdict in Chi Mak stands for the proposition that public domain data about defense articles can’t be exported to China. That’s simply wrong and betrays a fundamental misapprehension both of the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (“ITAR”) and what went on in the Chi Mak case. (Fair disclosure: I advised the Chi Mak defense team on the public domain issue in that case).

The Chi Mak case has engendered its fair share of confusion, and the latest victim is a trade law attorney who submitted a brief article to an export law newsletter that was published today. According to that article, the verdict in Chi Mak stands for the proposition that public domain data about defense articles can’t be exported to China. That’s simply wrong and betrays a fundamental misapprehension both of the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (“ITAR”) and what went on in the Chi Mak case. (Fair disclosure: I advised the Chi Mak defense team on the public domain issue in that case).

The article states:

The case sets the precedent that “technical data”, despite entering the “public domain”, requires an export license from the Directorate of Defense Trade Controls (DDTC) if China is the country of export. The jury’s finding reinforces this interpretation of the ITAR, and the subsequently heavy sentence by Judge Carmey reflects the seriousness the United States deems Chinese acquisition of military knowledge.

What the author apparently didn’t understand was that an instruction was given, and agreed to by the prosecutors, that if the data was in the public domain as defined by section 120.11(a) of the ITAR, it wasn’t subject to ITAR. So the jury’s conviction represents a determination that the items weren’t in the public domain as so defined.

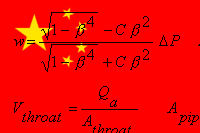

For example, the conference exception in section 120.11(a)(6) doesn’t cover every conference. That exception was at issue in the Chi Mak case because the documents were alleged to have been presented at an American Society of Naval Engineers (“ASNE”) conference According to that exception, a document is public domain if it is generally accessible to the public:

Through unlimited distribution at a conference, meeting, seminar, trade show or exhibition, generally accessible to the public, in the United States.

The jury may well have determined that the ASNE conference wasn’t “generally accessible to the public.”

The article goes even further astray when it tries to find a basis in the ITAR for a conclusion that public domain technical data can’t be exported to China.

§125.4 contains the licensing exemptions provision of ITAR. §125.4(a) states:

“The following exemptions [§125(b)(1)-(13)] apply to exports of technical data for which approval is not needed from the Directorate of Defense Trade Controls. These exemptions, except for paragraph (b)(13) of this section, do not apply to exports to proscribed destinations under § 126.1 of this subchapter…”

So if §125.4 is the exclusive exemption section of the ITAR, and China is excluded from any exemption as a country listed in §126.1, then it follows all technical data exported to China requires a license regardless of its presence in the public domain.

The critical problem with this analysis is that the definition which excludes public domain information from the definition of technical data isn’t an exemption mentioned in § 125.4. It isn’t even an exemption at all or it would be covered by section 126.1 itself, as the prosecutors initially argued, which notes that the “exemptions” in the ITAR aren’t applicable to China and the other proscribed countries.

Rather public domain material is excluded from the definition of technical data covered by the regulations. Exemptions are exceptions to licensing requirements for technical data otherwise subject to ITAR such as, for example, technical data being returned to the original source of import or technical data exported in furtherance of an approved technical assistance agreement. But if information is public domain under § 120.11, it isn’t technical data at all under § 120.10, and it can be exported without license and without reference to any exemptions.

A case that makes clear the difference between a definitional exclusion and an exemption is the way that the USML handles the QRS-11 quartz rate sensor navigational chip. There is now a note to Category VIII(e) that excludes such sensors when, among other things, they are integrated into a civil aircraft. The reason for this was to permit Boeing aircraft (all of which were equipped with the QRS-11 chip) to be exported to China. If the note is seen as an “exemption” for sensors in civil aircraft rather than as a definitional exclusion from the USML, then § 126.1 would proscribe exports of those planes to China, which was not the result contemplated by DDTC when it added that note to the USML

In short, exemptions and definitional exclusions are two very different things in the ITAR and you confuse them at your peril as did the author of the article in question. Frankly he should have been suspicious of his own conclusion because by his reasoning if someone tells a Chinese national that the B-2 stealth bomber has a “bat-wing” shape to reduce its radar cross-section, that person would be committing a criminal act, even though everyone who hasn’t spent the last two decades in a cave in Siberia is aware of the shape of a B-2 bomber and its purpose.

Posted by

Posted by  Category:

Category:

For all the time that we export lawyers spend trying to inculcate into our clients the concept of export red flags, it’s heartening to see that pay off. And it certainly did payoff in the

For all the time that we export lawyers spend trying to inculcate into our clients the concept of export red flags, it’s heartening to see that pay off. And it certainly did payoff in the  The saga of the government’s ill-fated prosecution of Alex Latifi and his company Axion Corporation continues. The federal district court judge delivered yet another forceful gavel whack to the hands of the prosecutors and

The saga of the government’s ill-fated prosecution of Alex Latifi and his company Axion Corporation continues. The federal district court judge delivered yet another forceful gavel whack to the hands of the prosecutors and

The Second Circuit issued an opinion on March 19 interpreting the sentencing guidelines applicable to violations of the Arms Export Control Act. That case,

The Second Circuit issued an opinion on March 19 interpreting the sentencing guidelines applicable to violations of the Arms Export Control Act. That case,