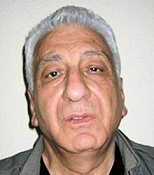

ABOVE: Monzer al-Kassar

An article that I just noticed in the February 8 issue of The New Yorker, tells the fascinating story of a D.E.A. sting operation conducted in Spain against Monzer al-Kassar, the notorious arms dealer alleged to have sold weapons both to the Achille Lauro terrorists and to the United States as part of the Iran-Contra affair. Kassar was arrested in Spain, extradited to the United States, and convicted in a Manhattan court to thirty years in prison on charges that he conspired to sell arms to FARC, a paramilitary terrorist group in Colombia.

The whole story is worth reading, but several details in the article are of particular note. First, the article emphasizes that arms dealers can be elusive because they structure their deals to comply with the laws of the countries in which they reside, negotiating sales from one country to another without ever leaving their home base where the brokering transactions are perfectly legal.

Second, and I know this will come as a shock, corrupt countries readily sell end-user certificates to arms dealers and certain arms manufacturers don’t even bother to read the end-user certificates that they demand. In one instance, Kassar bought weapons using an end-user certificate from the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen even though the DPRY had ceased to exist two years earlier when North and South Yemen reunited. One of the D.E.A. undercover agents almost blew his cover when he told Kassar that the Nicaraguan end-user certificate to be used in the FARC transaction had cost several million dollars.

Kassar scoffed, saying that with that kind of money he “could have bought a whole country.â€

Third, Kassar was caught because he abandoned his ordinary caution and allowed himself to be taped agreeing to sell arms that the undercover agents told Kassar would be used by FARC to kill Americans. As the reporter for the article stated:

Everyone I spoke to who has worked with Kassar over the years expressed surprise that someone so cautious could be caught on tape agreeing to sell weapons to the FARC. One possible explanation is that, compared with the last decades of the twentieth century—when conflicts in Africa, Europe, and the Middle East generated steady revenue—these are difficult times for weapons traffickers. When Samir first approached Tareq al-Ghazi in Lebanon, Ghazi told him that Kassar had been struggling to maintain his profit margins.

A diminished demand for black-market weapons may be driving other arms traffickers to assume risks that they would never have taken in the past. A year after the capture of Kassar, the S.O.D. team arrested Viktor Bout, the Tajik arms dealer, in Bangkok—using the same sting. (Bout asserts his innocence, and, to date, the Thai government has refused to extradite him.)

Kassar maintains his innocence and continues to insist that he was playing along with the D.E.A undercover agents in order to turn them in to Spanish authorities.

Permalink

Permalink

Copyright © 2010 Clif Burns. All Rights Reserved.

(No republication, syndication or use permitted without my consent.)

Posted by

Posted by  Category:

Category: